The Diuguids of Ghent, Kentucky

Skip’s grandfather, Hiram Diuguid, was born on the same sprawling farm on which he’d end up spending his entire life. It was a hundred acres of field and forest, and Skip’s very first memory of the United States would take place in these Kentucky woods. It was Christmas 1920, and her granddaddy Hiram said they should go out and cut down a tree to decorate. She was excited about the prospect of walking the woods with this sweet and gentle man, but when it came time to go, instead of asking Skip to join him, he invited her older brother Hiram. To this day, she can still remember the pang of jealousy she’d felt even at three years old.

Skip’s grandparents: Hiram Diuguid and Emma McCann Diuguid circa 1910

Hiram was only the second generation of Diuguids in Kentucky. The Diuguids had been a Virginian family for over a century before that. The first Diuguid in America, William Diuguid, left his home in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1740 on a journey across the Atlantic that could last six weeks if the headwinds were in their favor, or up to four months if they met foul weather. When he finally landed at the harbor in Jamestown, he sought out his first-cousin Patrick Henry and lived with him while he established himself in this new country. William Diuguid purchased prime land near Appomattox, right where the stage coach road crossed the James River with a covered bridge. It was a strategic place to settle down. With all the river traffic, he soon built a successful mercantile business and even became influential enough to get the town named after him when he died: Diuguidsville.

From the sea-faring Scottish immigrant William Diuguid to Skip’s grandfather Hiram in Kentucky, there were two generations: George Diuguid and Jacob Diuguid. George served in the local militia in the Revolutionary War for nearly three weeks, but then hired a substitute, John Basshaw, to fight in his place for the remaining months. He paid Basshaw a hundred dollars in property to fight, another indication that the Diuguids were already amassing some wealth. In the years after the Revolution, George’s son youngest Jacob was born in 1812. He would marry four times of the course of this life: when his first wife died of tuberculosis and their daughter soon afterwards of scarlet fever, Jacob relocated with his only living child, James Edwin, to Ghent (pronounced like gentle) on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River in 1852. It’s there that our Hiram was born.

Hiram was only ten at the outbreak of the Civil War. He was too young to serve, and his father, at 50, was too old. His older brother James Edwin Diuguid, however, was not as fortunate. He enlisted early in the war in the summer of 1862. He was a private in the Confederate calvary, and would be taken prisoner three times in one year: first, on June 24, 1864 in Georgia, then again on October 12 in Tennessee, and lastly, after the Battle of Nashville on December 15, 1864, along with over 4,000 other Confederate troops. Despite repeated captures, he managed to survive the war and would return home to Ghent.

After the Civil War, the Diuguids were by far the wealthiest branch of our family tree. It’s a stark contrast when we look at the 1870 census for Jacob Diuguid compared to all his contemporaries in our family tree. The census-taker asked each head-of-household how much their property was worth. In North Carolina, for example, John William Boyles reported $2000. Down in Laurens, South Carolina, W. H. Langston had $2,500. But our family in Ghent had far more, Jacob Diuguid, an astounding $16,120, eight times as much as many of our other relatives. Much of this wealth was generated from the people Jacob enslaved to work for him on his 225-acre plantation more than likely growing corn and tobacco. We know that Jacob owned at least sixteen people before Emancipation, including six children of mixed race.

Hiram was born into this wealth in 1852 and would become the president of the Ghent Deposit Bank, owning a farm right outside of town on land neighboring his father’s plantation. In the 1880s, Hiram bought land down east of Lubbock, Texas, where he grew cotton or tobacco, and where he spent every fall for the last fifty years of his life. The trip from Ghent would take him nearly a week just one way, as the trains snaked through stations in Memphis, Little Rock, Dallas, and finally into Lubbock.

Hiram died three months after his wife Emma in 1937, the same year Ghent Deposit Bank was forced to close in aftermath of the Great Depression. He came down with a cold while visiting his daughter Louise and Alva in Laurens passed away unexpectedly. Louise, sick herself, was unable to escort her father’s body back home, so Alva rode alone on the train back to Kentucky.

Not as much is known about Emma Estelle McCann. Skip called her namesake Granny, and she had the reputation of being traditional in her musical tastes and conservative in her ideas on women in the workforce. She was a teacher for over six decades years at the Baptist church they attended, and was well regarded by the congregation. She very well may have considered her greatest achievement to be her two daughters, both of whom went on to become active in their own churches: one daughter marrying a preacher, the other marrying a missionary to Brazil.

Tip: You can click on each photo to enlarge and read details. If you download the image, you can see it at even higher resolution.

James Edwin Diuguid, Hiram’s half-brother

From https://www.dolmarvadesign.com/jrspp-towns-villages/

Diuguidsville was a short-lived town. It was a bustling place for more than fifty years and boasted sixteen houses, three general stores, two groceries, a tavern, a “house of private entertainment”, and a tobacco warehouse. During the Civil War, when the people of Diuguidsville heard that Union troops were planning to cross the James River on the covered bridge right in front of William Diuguid’s house, they burned it down preventing the troops from reaching Appomattox Court House. Soon after the War, shipping and commerce on the James River declined, and so did the town of Diuguidsville. There's a historical marker there today that can be found at 37° 32.097′ N, 78° 49.65′ W. in Bent Creek, Virginia, in Appomattox County. You can find the marker at the intersection of Richmond Highway (U.S. 60) and State Highway 26, on the right when traveling south on Richmond Highway.

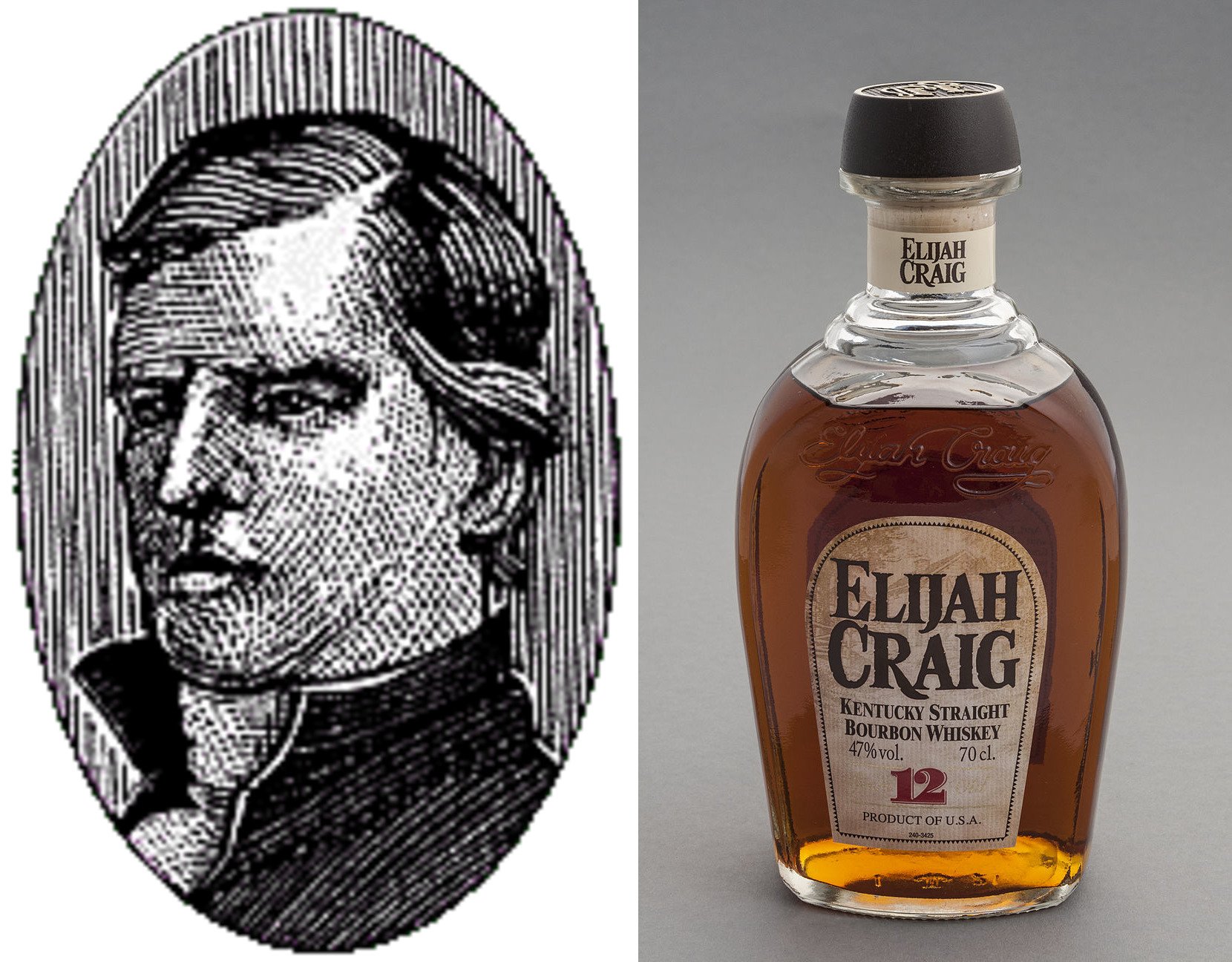

Along with Patrick Henry, it is through the Diuguid line that we are related to several notables: Daniel Boone, Frank and Jesse James, and Elijah Craig— the Baptist preacher and self-declared inventor of bourbon whose company still produces whiskey to this day.